Charging Into Policy Risk and Uncertainty

The President has used a policy failure of the 1800s and applied it to today’s modern economy.

On the campaign trail, President Donald Trump spoke fondly of the “McKinley” tariffs which were in imposed in the 1890s. This was when the U.S.’s leading exports were corn, cotton and meat. By 2020 the U.S.’s leadings exports were manufactured items such as aircraft and mechanical appliances.

During McKinley’s period the leading communications device was the telegraph, steam ships were used to cross the Atlantic and the primary mode of transportation was a horse and buggy.

By 2020 just in time delivery was common in supply chains, international flights are the most common mode of foreign travel and the I-phone includes material sourced from more than forty countries.

Background

After WWII, the U.S. and other victors created the international system of trading called the Bretton Woods agreement. This process included the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade or the (GATT).

The mission of the GATT was to reduce tariff and non-tariff barriers in international trade and investment. This was the US creating the world in its own image.

The US and Great Britain created the GATT with the goal of spreading peace and prosperity internationally. While the goal was public spirited, it originated in self-interest (the US and Great Britain stood to benefit the most).

At the time Washington’s rivals were dead in the water. The scorched earth bombing of WWII leveled the Eurasian continent and Japan. The U.S. hoped the Marshall Act would help allies get on their feet again and eventually become happy, free-trading, capitalists. This allowed the US to be the world’s largest exporter.

The theories of Adam Smith and David Ricardo became international policy, which some labeled the “Washington Consensus.” Wealth and incomes grew in the Western world. Free trade expanded internationally and regionally, in blocks like the European Union, NAFTA and Mercosur.

In the 1970s wealth and income disparities grew in the West, creating definite winners and losers in the globalizing economy. These disparities initially mirrored educational differences but evolved into stagnant wealth favoritism and class warfare.

As the wealth of U.S. allies grew in Japan and Europe, the U.S. became restless as the leader of expanded globalization. As China’s economic fortunes expanded through “unfair” trade practices, calls for retaliation and redress reached a fever pitch. This growing resistance led to the elections of Donald Trump and Joe Biden.

After 2008 the post WWII international trade system went into reverse as counties, like the UK, left the union of free trading countries in the EU and Venezuela was suspended from Mercosur.

Barriers to international trade and investment increased in the wake of the Coronavirus pandemic. Reshoring, friendshoring, resource nationalism and export bans emerged and expanded.

Present

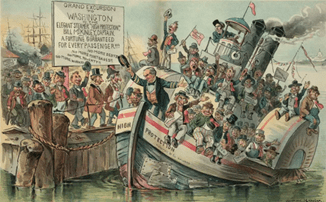

A growing international consensus of less free trade and investment has spread. As more of the world moves in a “beggar thy neighbor” direction, competitive advantages will decline and economies of scale will disappear.

In a “beggar thy neighbor” world each country looks out for itself exclusively. As this sentiment grows US exports will decline and the cost of US imports will increase.

Economic Fallout

How will this show up economically?

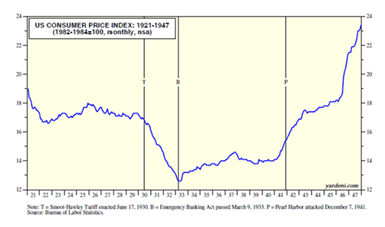

In the short term, tariffs will create chaos for consumers, in the long run tariffs will impact producers. As tariffs, and tariff concerns, grow investors will cut back on production, incomes will decrease and unemployment will rise.

Mass manufacturing requires patient entrepreneurs who know their investments will lose money until they can ramp up production to effectively capture economies of scale. It may have cost $50 million to produce the first Model T Ford, but the 5000th car could be made for less than $1000.

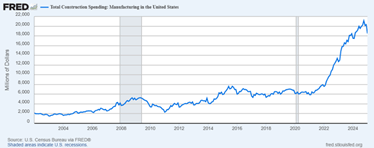

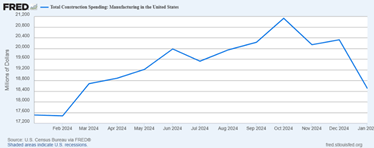

Not surprisingly US investments in manufacturing have been declining since last year. Construction of manufacturing facilities, like assembly lines for washing machines, started declining in October of last year. This is when it first became apparent Donald Trump would become the next President. Do investors and corporate executives have Trump derangement syndrome?

It is more likely that they were worried about policy risk. This has manifested in President Trump’s tariffs announcements and reversals. The President uses policy announcements and surprises to keep US competitors off balance.

For a long-term investors laying out billions of dollars the uncertainty is unnerving. Risk can theoretically be measured, uncertainty cannot. Recent events have injected a massive element of caution into their calculations.

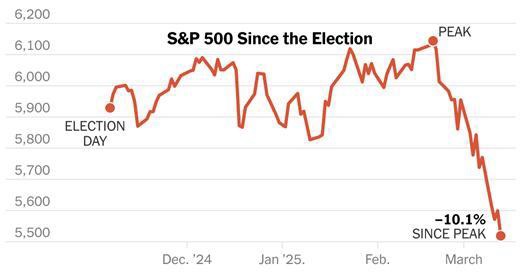

In the heat of the new tariff announcements, Economist Noah Smith said, “small business investment plans are crashing and manufacturers are crashing hard.” Smith explained the stock market can “take the long view.”

Those who anticipate supply shock induced by tariffs, could cause a demand shock. This is when buyers, be they consumers or corporations, go on strike. The conservative American Enterprise Institute wrote, “Trump also seems blind to the idea that markets and economic agents abhor uncertainty.”

A survey of U.S. Chief Executive Officers found their opinion on the current business conditions is as low as it has been since the pandemic. The Dallas Federal Reserve reported that uncertainty is leading to less investment in energy production. One executive called uncertainty the “keyword to describe 2025” and added our investors “hate uncertainty.”

Economist Stephen Roach stated, “Uncertainty is the enemy of decision making.” He warned “businesses when faced with uncertainty will not make the big fixed-cost decisions to expand plants and engage in construction of new facilities to expand our productive capacity.”

The U.S. is not in a recession yet. But, continued uncertainty, combined with less consumer spending and business spending will lead to one.

If the Trump pledged tariffs are actually implemented by the U.S and its trading partners retaliate as promised, long term investments can decline further and layoffs could expand.

Hopefully, cooler heads will prevail.